How Mentor International School Teaches Problem-Solving Through Science

At Mentor International School (MIS) in Hadapsar, we believe that science education serves a purpose far greater than memorizing facts or preparing for examinations—it’s about developing problem-solving capabilities that students will use throughout their lives. Our approach to science teaching transforms classrooms into laboratories of curiosity where students learn to think critically, ask meaningful questions, test hypotheses, and develop solutions to real-world challenges.

Our Philosophy: Science as a Thinking Tool

Traditional science education often emphasizes content coverage—students memorize facts, formulas, and procedures to reproduce on tests. While foundational knowledge matters, this approach fails to develop the analytical and problem-solving skills that define scientific thinking.

At MIS, we view science primarily as a methodology for understanding and solving problems. Our students don’t just learn what scientists have discovered; they learn to think like scientists—observing carefully, questioning assumptions, designing investigations, analyzing evidence, and drawing reasoned conclusions.

The MIS Scientific Problem-Solving Framework

Our approach to teaching problem-solving through science follows an integrated framework that develops multiple interconnected capabilities:

1. Cultivating Curiosity and Question Formulation

Problem-solving begins with recognizing that problems exist and asking the right questions.

How we teach this:

- Wonder Walls: Each classroom has dedicated spaces where students post questions about phenomena they observe—”Why do leaves change color?” “How do birds know where to migrate?” “Why does ice float?”

- Question Quality Development: We explicitly teach students to transform vague wonderings into testable scientific questions. “Why is the sky blue?” becomes “What property of air causes different wavelengths of light to scatter differently?”

- Real-World Connection: We constantly connect classroom concepts to observable phenomena, encouraging students to question everyday occurrences rather than accepting them passively.

- No Stupid Questions Culture: We create psychological safety where all questions are valued, teaching students that curiosity is strength, not weakness.

Example: When a Grade 4 student asked why water droplets on windows sometimes move upward, instead of dismissing it or providing a quick answer, our teacher guided the class in investigating surface tension, adhesion, cohesion, and temperature effects—turning one question into weeks of engaged exploration.

2. Observation and Data Collection Skills

Effective problem-solving requires noticing details, recognizing patterns, and gathering information systematically.

How we teach this:

- Observation Stations: Students regularly engage with materials they can examine closely—plant growth sequences, rock samples, chemical reactions, living organisms—learning to describe observations precisely using scientific vocabulary.

- Drawing as Observation: We require detailed scientific drawings that force students to notice details they might otherwise overlook. Drawing a leaf requires observing vein patterns, edge shapes, surface textures, and color variations.

- Measurement and Quantification: Students learn to gather quantitative data using tools—thermometers, rulers, balances, timers—understanding that precise measurement enables analysis and comparison.

- Multiple Observation Types: We teach students to observe across modalities—visual appearance, physical properties, behavioral patterns, changes over time, interactions with other substances or organisms.

Example: In our Grade 3 unit on plant growth, students don’t just glance at plants occasionally. They measure height daily, count leaves weekly, photograph growth stages, describe color and texture changes, and record environmental conditions—developing systematic observation habits.

3. Hypothesis Formation and Prediction

Problem-solving requires making educated guesses about cause-and-effect relationships based on prior knowledge and observations.

How we teach this:

- Explicit Hypothesis Structure: Students learn to formulate hypotheses in testable formats: “If [I change this variable], then [this outcome will occur] because [this is the underlying mechanism].”

- Evidence-Based Reasoning: Before experiments, students articulate why they predict particular outcomes based on what they already know, connecting new investigations to prior learning.

- Multiple Hypotheses: We encourage generating several possible explanations for phenomena rather than fixating on single answers, developing flexibility in thinking.

- Prediction vs. Preference: We teach students to distinguish between what they hope will happen and what they logically expect based on evidence.

Example: Before testing which materials make the best insulation, Grade 5 students formulated hypotheses connecting material properties (thickness, air pockets, density) to predicted insulation effectiveness—demonstrating reasoning rather than random guessing.

4. Experimental Design and Variable Control

Solving problems scientifically requires designing fair tests that isolate variables and produce reliable evidence.

How we teach this:

- Variable Identification: Students learn to identify independent variables (what they change), dependent variables (what they measure), and controlled variables (what they keep constant).

- Fair Testing: Through repeated practice, students internalize that changing multiple variables simultaneously makes it impossible to determine causation.

- Control Groups: We teach why control groups matter, helping students design experiments that include appropriate comparisons.

- Iterative Design: When initial experiments produce confusing results, we teach students to refine their approach rather than giving up—developing persistence and methodological thinking.

Example: When Grade 6 students investigated factors affecting plant growth, different groups isolated single variables—light intensity, water quantity, soil type, temperature—while controlling all other factors, then shared results to build comprehensive understanding.

5. Critical Analysis and Evidence Evaluation

Problem-solving requires interpreting data objectively, recognizing patterns, and drawing warranted conclusions.

How we teach this:

- Data Organization: Students create tables, graphs, and charts to organize data visually, making patterns more apparent.

- Pattern Recognition: We explicitly teach students to look for trends, correlations, outliers, and relationships within data.

- Evidence vs. Explanation: Students distinguish between describing what they observed (evidence) and explaining why it happened (interpretation).

- Uncertainty and Error: We teach that unexpected results aren’t failures but opportunities for learning, helping students analyze potential sources of error and refine methodology.

- Supporting Claims with Evidence: Every conclusion must be justified with specific data, teaching students to argue from evidence rather than assertion.

Example: When a chemistry experiment produced unexpected results, rather than dismissing it as “wrong,” our Grade 7 students analyzed what might have caused the discrepancy—impure reactants, measurement error, temperature variation—developing troubleshooting skills.

6. Collaborative Problem-Solving

Most real-world problem-solving happens in teams; students must learn to work effectively with others.

How we teach this:

- Group Investigations: Students regularly work in teams on complex problems requiring collaboration—designing experiments together, dividing responsibilities, sharing findings.

- Peer Review: Students present findings to classmates who ask questions, suggest alternative interpretations, and identify gaps in reasoning—mimicking scientific peer review.

- Diverse Perspectives: We intentionally create diverse groups, teaching students that different backgrounds and thinking styles strengthen problem-solving.

- Communication Skills: Students learn to explain their thinking clearly, listen actively to others’ ideas, provide constructive feedback, and integrate multiple perspectives.

Example: Our annual Science Fair requires student teams to identify community problems, design investigations, and propose evidence-based solutions—developing collaborative problem-solving skills.

Subject-Specific Problem-Solving Approaches

Physics teaching at MIS emphasizes understanding fundamental principles and applying them to solve design challenges.

- Engineering Design Process: Students identify problems, brainstorm solutions, build prototypes, test performance, analyze results, and iterate improvements.

- Real-World Applications: Rather than abstract concepts, students explore how physics principles solve actual problems—designing bridges that support weight, creating insulation for temperature control, building simple machines that reduce required force.

- Mathematical Modeling: Students learn to represent physical relationships mathematically, using equations not just to calculate but to predict and analyze behavior.

Example: Grade 8 students designed earthquake-resistant structures using popsicle sticks, applied forces to test stability, analyzed failure points, and redesigned based on data—integrating physics concepts with engineering problem-solving.

Chemistry and Material Science

Chemistry teaching emphasizes understanding how substances interact and how that knowledge solves practical problems.

- Predicting Reactions: Students learn to predict products based on reactant properties, developing logical thinking about molecular interactions.

- Practical Applications: Investigations connect to real uses—using acid-base reactions for cleaning, exploring polymers and their properties, understanding how food preservation works chemically.

- Environmental Problem-Solving: Students investigate pollution, water quality, and sustainable materials, applying chemistry to address environmental challenges.

Example: Grade 9 students investigated water purification methods, testing different filtration materials and chemical treatments, then designed optimal systems for removing specific contaminants—applying chemistry to solve real problems.

Biology teaching emphasizes systems thinking and understanding how living systems adapt and respond to challenges.

- Ecological Problem-Solving: Students investigate ecosystem relationships, biodiversity loss, invasive species, and conservation strategies.

- Human Biology Applications: Learning anatomy and physiology connects to health problem-solving—nutrition, exercise, disease prevention.

- Adaptation and Evolution: Understanding how organisms solve survival problems through adaptation develops flexible, creative thinking.

Example: Grade 7 students investigated declining bee populations, researched causes, and designed school garden modifications to support pollinators—combining research with practical problem-solving.

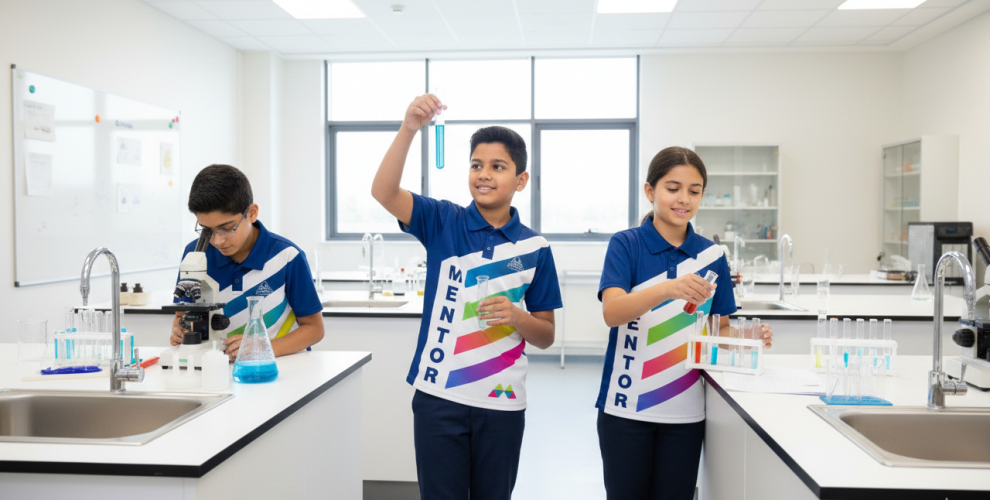

Our Laboratory and Hands-On Approach

At MIS, science happens through direct experience, not passive observation.

Our science laboratories feature:

- Modern equipment: Microscopes, sensors, measurement tools enabling authentic investigation

- Safety infrastructure: Proper ventilation, safety equipment, and protocols ensuring safe exploration

- Flexible spaces: Configurations supporting individual work, group collaboration, and whole-class demonstrations

- Technology integration: Data collection sensors, simulation software, digital microscopy expanding investigation possibilities

Rather than cookbook procedures, our labs emphasize genuine inquiry:

- Students often design their own investigation procedures rather than following predetermined steps

- Open-ended investigations allow multiple approaches and outcomes

- Students encounter and troubleshoot real methodological challenges

- Emphasis on thinking process rather than getting predetermined “correct” results

Science isn’t occasional but integrated throughout the curriculum:

- Weekly laboratory sessions for all grade levels

- Science concepts reinforced through practical application across subjects

- Regular opportunities for independent and group investigation

- Science integrated into outdoor education and field experiences

Project-Based Learning in Science

Extended projects develop deep problem-solving capabilities impossible in single class periods.

Our school-wide Science Fair exemplifies problem-solving through science:

- Students identify genuine questions or problems they want to investigate

- They design complete investigations including methodology, data collection, analysis, and conclusions

- Projects span weeks, developing sustained engagement with complex problems

- Presentation to community members develops communication skills

- Judges provide feedback on scientific reasoning and methodology

Complex problems rarely fit neatly into single subjects:

- Environmental Projects: Combine biology, chemistry, mathematics, social studies addressing real environmental challenges

- Engineering Challenges: Integrate physics, mathematics, design, technology solving practical problems

- Health and Nutrition: Connect biology, chemistry, physical education, life skills addressing wellness challenges

Example: Our Grade 6 “Sustainable School” project had students audit school energy use, investigate renewable alternatives, calculate costs and environmental impact, and present recommendations to administration—combining science with mathematics, economics, and communication.

Teaching Problem-Solving Dispositions

Beyond specific skills, we cultivate attitudes essential for effective problem-solving:

- Struggle is normal: We normalize that problem-solving involves confusion and setbacks

- Mistakes are data: Unexpected results teach us something valuable about the problem

- Ability develops: Scientific thinking improves with practice and effort

- Persistence matters: Most important discoveries come through sustained effort

Scientific Skepticism and Open-Mindedness

- Question everything: Healthy skepticism about claims and assumptions

- Demand evidence: Accepting conclusions only when supported by data

- Revise thinking: Willingness to change beliefs when evidence warrants

- Multiple perspectives: Considering alternative explanations before concluding

- Imagination matters: Hypothesis generation requires creative thinking

- Multiple approaches: Same problem can be investigated many ways

- Novel connections: Breakthroughs often come from unexpected connections

- Aesthetic appreciation: Beauty exists in elegant solutions and experimental design

Assessment That Develops Problem-Solving

Our assessment approach reinforces problem-solving rather than undermining it:

We evaluate:

- Quality of questions students generate

- Appropriateness of investigation methodology

- Rigor of data collection and analysis

- Reasoning quality in drawing conclusions

- Ability to identify limitations and improvements

Rather than only paper tests, students demonstrate learning through:

- Designing and conducting investigations

- Solving novel problems requiring application of principles

- Analyzing unfamiliar scenarios using scientific reasoning

- Communicating scientific ideas to various audiences

Feedback That Guides Improvement

Assessment provides specific, actionable feedback:

- Identifying reasoning gaps or methodological weaknesses

- Suggesting resources or strategies for improvement

- Celebrating strong problem-solving approaches

- Setting goals for developing capabilities

Parent Partnership in Problem-Solving Development

We recognize that problem-solving development requires home-school collaboration:

- Communicating Learning Goals: Sharing what problem-solving skills students are developing

- Suggesting Home Extensions: Recommending activities families can do together

- Celebrating Curiosity: Encouraging parents to welcome questions and exploration

- Modeling Problem-Solving: Helping parents understand their role in fostering analytical thinking

Our approach produces students who:

- Approach novel challenges systematically rather than with anxiety or resignation

- Ask meaningful questions about phenomena they encounter

- Distinguish reliable information from misinformation

- Work effectively in teams to solve complex problems

- Persist through difficulties rather than giving up quickly

- Apply scientific reasoning across academic subjects and life situations

- View problems as opportunities for learning and growth

Conclusion: Science Education for Life

At Mentor International School in Hadapsar, we teach science not primarily to create scientists (though some students will pursue scientific careers) but to develop capable problem-solvers who approach challenges rationally, evaluate evidence objectively, think creatively, and persist through difficulties.

The problem-solving capabilities developed through our science program serve students throughout their lives—in future academics, in careers across all fields, in personal decision-making, and in contributing to solving societal challenges.

We invite families to visit MIS and experience our science program firsthand—observe students engaged in authentic investigation, see our well-equipped laboratories, meet our passionate science faculty, and discover how we develop problem-solving capabilities that last a lifetime.

Contact Mentor International School today to learn more about how our distinctive approach to science education develops the analytical, creative, persistent problem-solvers the world needs. Your child’s journey toward scientific thinking and effective problem-solving begins here.